grand Shots on Press

grand Shots on Press

In August 2024, a fellow artist and freelance journalist in our GTA Community reached out to us

about writing an article on gaming photography, virtual photography, and nostalgia in the digital age.

The interview was first published online, and a year later, the article was selected for the Summer 2025,

6th Issue of Wired Czechoslovak.

Thanks to Zuzana Ľudviková, Grand Shots appeared in printed media for the first time!

Read the article from the website:

Shots of the Printed WIRED Article: Number 6 Summer 2025

Aim, press the shutter and – click! In the viewfinder of artists whose terrain is video games Article from Zuzana Ľudviková for Wired.cz

English translations are provided by the author of the article.

05/10/2024

A new type of player has joined the gaming world. He is not interested in missions and tasks from developers, but still wanders the virtual streets for hours. His only goal is to catch the sharpest shot, through the camera viewfinder directly inside the game. For the growing community of virtual photographers, beats are a new kind of art. All they need is the screenshot function or one of the clever photo modes that game developers are increasingly cooking up for the gaming community, thanks to which shots from their games circulate on the Internet practically forever.

What kind of art is virtual photography?

What can game worlds tell us about our society?

And are games changing our relationship with what is really real?

Beauty in virtual ordinary The trend of virtual photography was popularized in the summer of 2020 by a group of documentary photographers who temporarily moved their studio to a virtual street during the covid-19 pandemic during the curfew and found new muses in the NPC characters of the western cowgirl Red Dead Redemption 2. However, the Internet hashtags #VirtualPhotoghraphy and #TheCapturedCollective on the social platform X and elsewhere are proof that virtual photographers had settled permanently in game worlds a few years earlier. Getting through missions to the end of the game is not in their sights, and instead they prefer to wait for the perfect light woven from ones and zeros or for an unexpected “glitch” (a technical error in the graphics card or game code) that temporarily changes the appearance of the game.

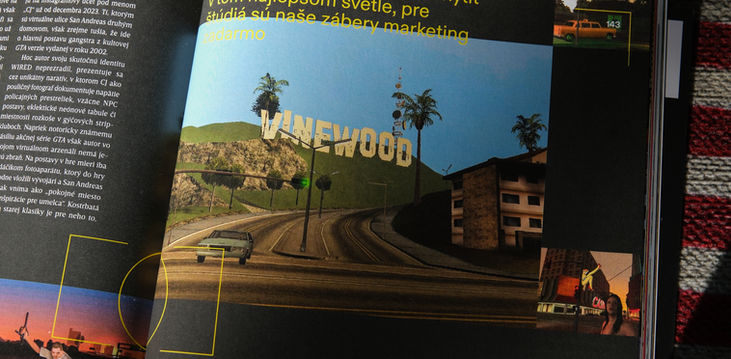

A unique example is the Grand Shots project with more than 30 thousand followers on the social network Instagram, which, through triptychs of city neighborhoods from more than twenty years of the game, seeks beauty in virtual custom and nostalgically presses on the most sensitive places of every die-hard fan of the Grand Theft Auto series. A slightly different mission Dynamic game visuals with angular characters and the transcendent melancholy of the American street have been added to the Instagram account under the name "CJ" since December 2023.

However, those for whom the virtual streets of San Andreas are their second home probably suspect that this is the main character of the gangster from the cult GTA version released in 2002. Although the author did not reveal his real identity to WIRED, he presents himself through a unique narrative in which CJ, as a street photographer, documents the tension of police shootouts, rare NPC characters, eclectic neon signs, or pleasure rooms in kitschy strip clubs. Despite the notorious violence of the GTA action series, the author does not have a single weapon in his virtual arsenal. He only aims the camera viewfinder at the characters in the game, which was originally inserted into the game by the developers, and on the contrary, he sees San Andreas as a “peaceful place full of inspiration for the artist”.

For him, the rough graphics of the old classic are what materialize the soul of the places and characters that he did not have time to get to know in depth during the game. Through their stories, the author of Grand Shots wants to show that even the old game still has something to offer, “if you look at it with new eyes”. He also admits to WIRED that through GTA he first felt his virtual existence: “I suddenly perceived the NPC characters as real people with stories that go beyond the game.” The more the author immerses himself in the game through the fictional character named CJ, the more tangible the virtual world of San Andreas becomes for him. It also helps that Grand Shots aren't just photos from an old video game that filled a hole in our childhoods - accompanied by music from the fictional San Andreas radio station inside the game, they're also part of a viral trend on Instagram.

Through photos and short reel videos, Grand Shots is a nostalgic wink at a new form of digital art that fans interact with daily on the social network. "We live in a time of harsh change, and coming across a game from our childhood through a project like Grand Shots is like coming home for a moment. Most gamers remember their gaming era as summers spent in front of a computer, which are also very formative for human identity," explains Lars de Wildt, a game scientist at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands who studies the impact of video games on religion, society and culture in games like Assassin's Creed, World of Warcraft and BioShock.

However, if you were to play GTA: San Andreas alone after years, there's a good chance you'd give up after three hours - whether it's a lack of time in your adult routine or a feeling that things will never be the same again. The polished nostalgic photos of Grand Shots can thus evoke a sense of nostalgia in any former player without devoting dozens of hours to the game that they no longer have, De Wildt believes. ...

...

The border between video games and the “real” world Does virtual photography change the gaming experience? Thomas Spies, a German virtual photographer and game scientist at the University of Cologne, does not draw a sharp line between the world of video games and “reality”. He sees the online and offline spheres as two interconnected worlds, since our daily lives are also defined by digital encounters and interactions that are no less real. In his work, he deliberately mixes them in order to understand what new games can tell us about virtual experiences, communities and worlds, but also about our society and our own identity.

His photo series Mimicry captures random passers-by or a supermarket clerk – both NPC characters from GTA V – staring intently into Spies’ camera, while their virtual portraits in a diptych are complemented by silent photographs of (real) plastic figurines. The decisive poses of GTA characters or the chilling mannequins thus raise many questions, for example, about what imitates a person better – a work of the real world or the virtual world? “We wouldn’t consider the mannequins we see in clothing stores to be real people. But is a virtual person in GTA more realistic than a mannequin? If I combine the two, I can remove the imaginary boundary that would otherwise divide them,” explains Spies, who captured the images for the series in boutique windows or in a weapons store in virtual Los Santos.

Americana is another similar series by a German virtual photographer, who, through GTA V, projects a critical image of how game developers represent society through familiar stereotypes and scenes reflecting reality, where poverty is omnipresent and American prosperity is a thing of the past. However, elements of artificiality never completely disappear from game worlds. This is also because the physics in games work differently, objects sometimes merge, and you usually don't find anything at all in beautifully rendered houses.

Online community of gaming enthusiasts Frenchman Ludovic Helme, who has been taking pictures of video games for five years, doesn't play one these days without taking one or twenty virtual snaps. He is always tempted by the feeling of absolute freedom to capture every millimeter at his own pace, which is not possible in the real world. "Virtual photography is much less restrictive and cheaper than that in the physical world," thinks Helme, who works from Osaka, Japan under the pseudonym Shinobi. "In a video game, you don't need a drone to take a photo from above, and you don't need an expensive camera or studio lights to get a sharp shot with good light. You just need one photo mode, with which you can do everything." Stop time, control the light, adjust the depth of field, contrast, camera position or use creative filters – however, each game has its own photo mode. Their quality and control options also depend on how much time and money developers invest in them. For example, those in popular games such as Horizon Zero Dawn or The Last of Us II from the development studio Naughty Dog work on the principle of “freezing the scene”, thanks to which the textures of avatars and surrounding objects are temporarily rendered in a much higher resolution (4K or even 8K).

Helme, with his five years of experience in virtual photography, sometimes helps development studios as a consultant – he has already participated in the development of photo modes for the games Flintlock: The Siege of Dawn or Deathloop. At the same time, the French virtual photographer sees the growth of virtual photography and more opportunities for cooperation with development studios as the success of a small online community of enthusiasts, which has gradually gained recognition from the gaming industry. “Since we also want to capture the game in the best light, our shots are free marketing for the studios,” comments Helme, who was hired by the game company Kepler Interactive specifically to shoot promotional shots for their game Flintlock. The reward for such assignments is usually access keys to the games – but Helme would not like it if the artistic value of virtual photos was turned into a business in order to catch free games.

Spies, who studies this community of virtual photographers as part of his own research, criticizes the way development studios profit from publicly shared shots from photographers, who are usually big fans of the games. “Studios deliberately improve their photo modes so that virtual photography becomes part of their ecosystem. This strengthens their own advertising and profit at the expense of the creative activity of the players,” believes the virtual photographer and game scientist. In academic circles, this is referred to as "playbour" - work through play that is often underappreciated and exploited by development studios. “While we own the image, they own the game”

We also see a grey area about who owns the copyright to the creations of virtual photographers. The fact is that the development studio and companies have the intellectual property rights, so they are the largest owner of the game content. “Although we, the virtual photographers, own the intellectual property rights to the image, which the development companies cannot use without our consent, we cannot just sell our photos, since they own the rights to the game,” Helme says. Helme’s photos breathe ethereal compositions of surreal worlds, mystical beings in the midst of battle or chillingly detailed portraits of characters, and they reach thousands of views on the social network X.

However, virtual photography primarily fulfills his need to create and he sees the dilemmas about copyright as an opportunity for new debates. He managed to find an interesting angle for this: “In virtual photography, you can express your creativity through the creativity of someone else – the development team and the game itself,” thinks Ludovic “Shinobi” Helme. Just like in the offline world, gaming reality can be perceived anew through virtual photography. For scientist and video game enthusiast Lars de Wildt, this is precisely the meaning of good photography, which transforms real life in a way that is almost unrecognizable – and connects bits with being.